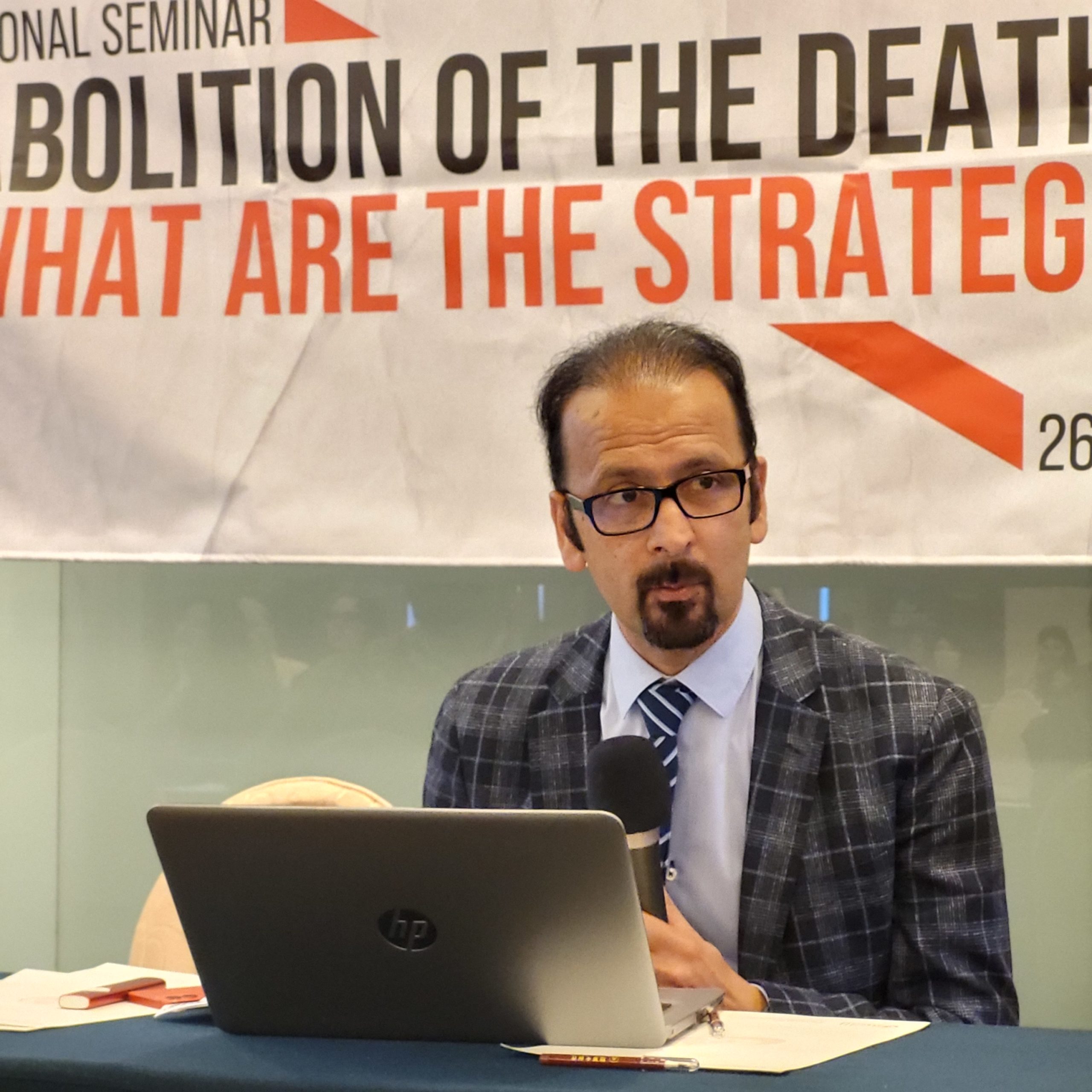

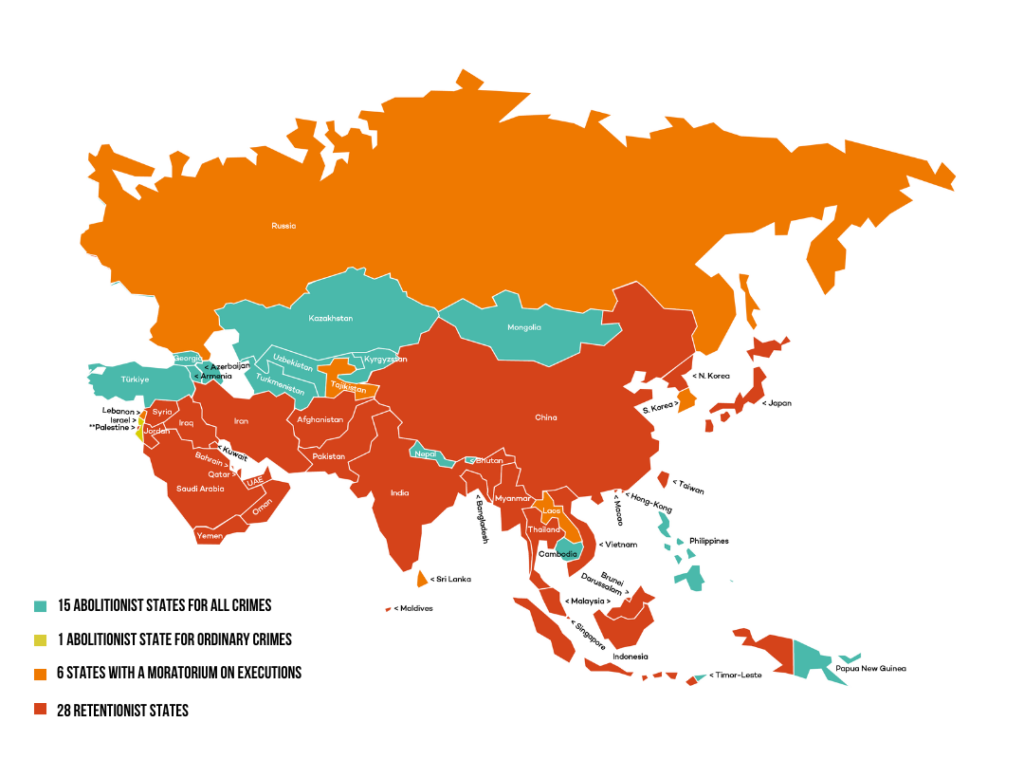

The death penalty in Asia: where do we stand?

While two-thirds of the world’s countries have abolished the death penalty in law or practice, Asia remains the region with the highest number of executions in the world, although this has not always been the case: at the seminar’s opening ceremony, Raphaël Chenuil-Hazan reminded us that the abolitionist trend began long before abolition in Europe under the Tang dynasty. Today, governments see capital punishment as an opportunity to consolidate their power and instil fear in their populations, ignoring international agreements and mostly justifying its retention by the war on drugs.

A disturbing resurgence of executions during waves of political repression

In 2021, at least 462 executions took place on the continent (not counting executions in China) and over 1,175 people were sentenced to death (figures for China, Iran, North Korea, Oman, Qatar, Syria and Thailand were not disclosed).

In 2022, a very high number of executions took place in particularly appalling contexts, notably in Iran (at least 582), in Myanmar (2), where executions resumed after a 34-year moratorium, and in Singapore, where 11 death row inmates were executed after a three-year pause, in violation of international law, notably during the execution of a mentally disabled death row inmate.

Positive advances herald the beginnings of an abolitionist trend

With almost a month to go previous to the regional seminar on the death penalty in Asia, the Malaysian government has passed a law replacing the mandatory death penalty with alternative sentences for 11 charges, including murder and terrorism, and giving judges the discretion to take into account mitigating circumstances and commute sentences for these crimes.

In the last two years, two countries have taken the step towards abolition. First Kazakhstan (2021), for all crimes, then Papua New Guinea (2022). In 2021, Sri Lanka renounced the death penalty for juveniles at the time of the alleged offence.

Small steps towards abolition have also been taken in some countries, such as Indonesia, where the adoption of a new penal code now provides for a ten-year probationary period in the event of a death sentence, before the sentence is confirmed or commuted. However, this is only a limited step forward, as it will not automatically be granted to all those sentenced to death. In India, the Supreme Court has called for death penalty reform, although 2022 saw the highest number of death sentences handed down by lower courts in 20 years. In October 2022, Pakistan passed a law criminalizing torture, which should have an impact on the application of the death penalty.

Two days of exchanges and testimonies between human rights defenders

The two-day seminar enabled all the abolitionist actors to exchange views on the application of the death penalty, and to discuss best practices for dealing with the authorities, civil society organizations and the general public.

Considering the intersectionality of struggles to abolish the death penalty in Asia

On the first day, panels made up of a diversity of abolitionists such as Parliamentarians, National Human Rights Institutions, activists, NGO spokespersons and former death row inmates, demonstrated through their arguments that our common mandate is sadly at the crossroads of many human rights struggles. Sexual violence, migratory phenomenon and the war against drug trafficking are often at the root of death sentences in the region, making gender, ethnic and religious minorities a tool of political manipulation by governments in power.

Discussions also revolved around strategies for establishing abolition in Asian countries. Dato’ Hasnal Rezua Merican Bin Habib Merican, Commissioner of the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM), recalled the colonial legacy of this sentence carried to national level by the British Empire, which remained unchallenged for forty years following independence in 1957: “The death penalty is a political instrument, so it is up to the government to put it on the agenda for political reform. […] We need to take strong measures now and enshrine abolition in law, because we don’t know who might one day come to power,” he asserted.

Workshops were also held on best practices for communicating with the press and new media, with a view to extending the fight to new sectors and involving citizens in a societal change that is favorable to all.

A road paved with obstacles to abolition

In 2022, the use of the death penalty was particularly worrying on the Asian continent. This second day was dedicated to the obstacles faced by activists in carrying out their advocacy work. A long session devoted to the situation of lawyers defending people sentenced to death raised many challenges: in several countries, lawyers are the target of intimidation by their own governments, as in the case of Mr. Ravi, a lawyer in Singapore. Banned from practising for five years, he continues to advocate on behalf of death row inmates. In Indonesia, Yosua Octavian, Caseworker (LBH Masyarakat), points out that not all lawyers are in favor of abolishing the death penalty, or are afraid to take on such cases for fear of reprisals. Pretty Tioria Sirait, Deputy Coordinator of Advocacy (KontraS), also pointed out that some lawyers collaborate with the police, going against the interests of their clients. In the country, while lawyers are obliged to accept pro bono cases, there are no penalties for non-compliance.

Data collection and transparency regarding death penalty cases in countries run by authoritarian governments that can at times be illegitimate, also represent a major obstacle to the advancement of the abolitionist struggle in the region. In Myanmar, for example, since the military dictatorship took power, it has become very difficult to verify data, as the families of those executed fear that the name of their loved one will be divulged on social networks. Deliberate Internet blackouts, attacks on freedom of expression and disinformation are also factors slowing down the work of abolitionist activists.

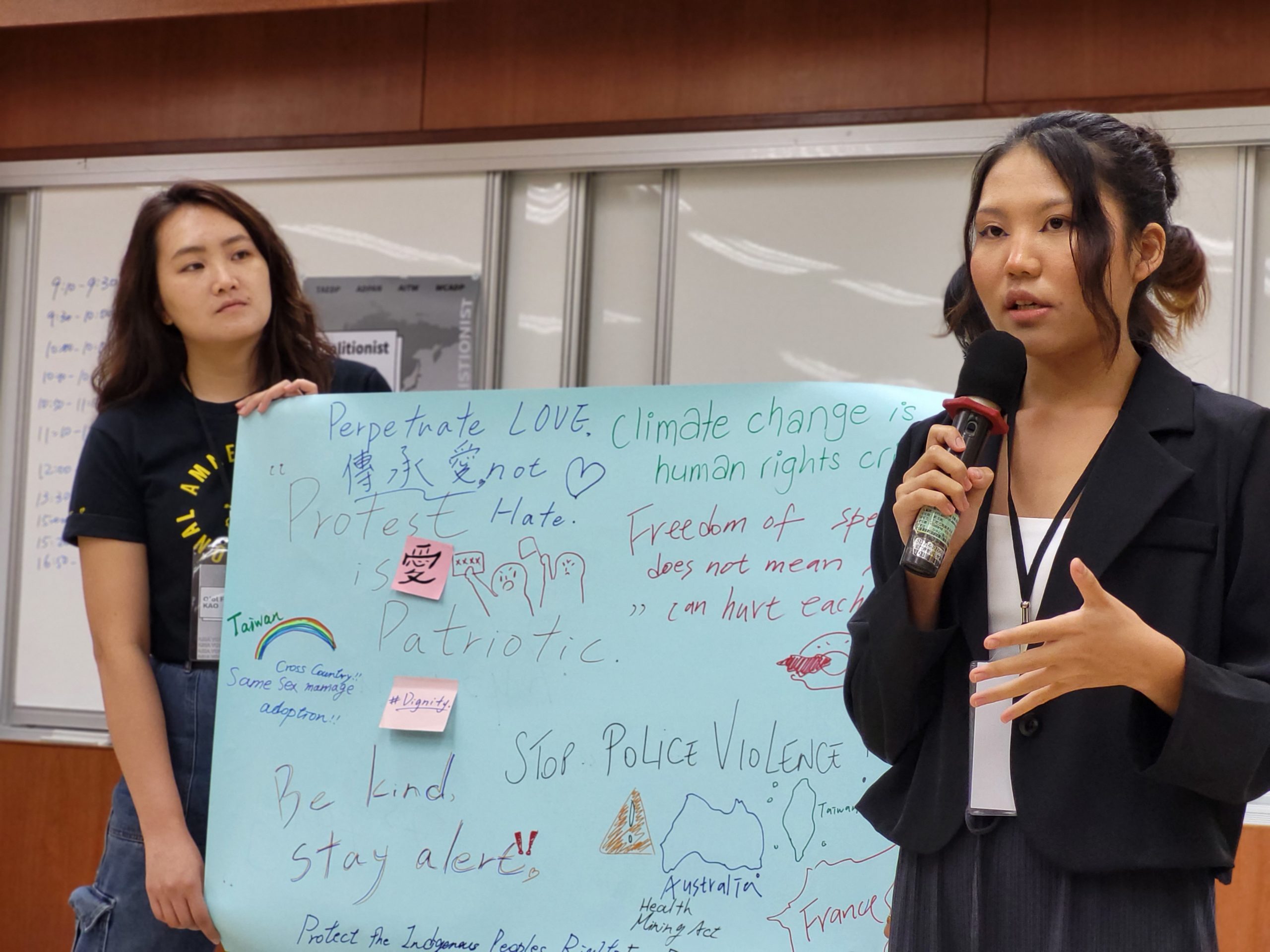

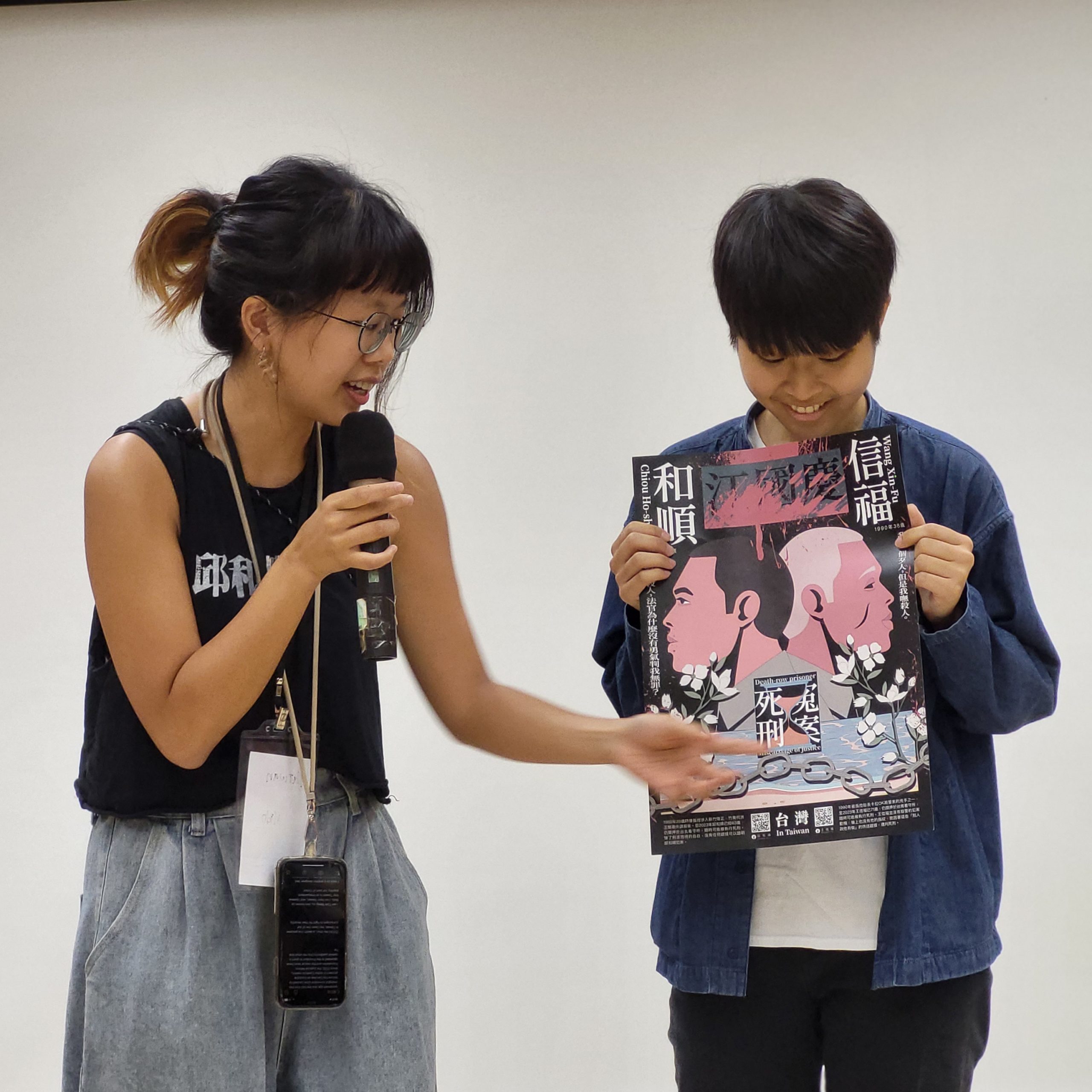

Young people against the death penalty

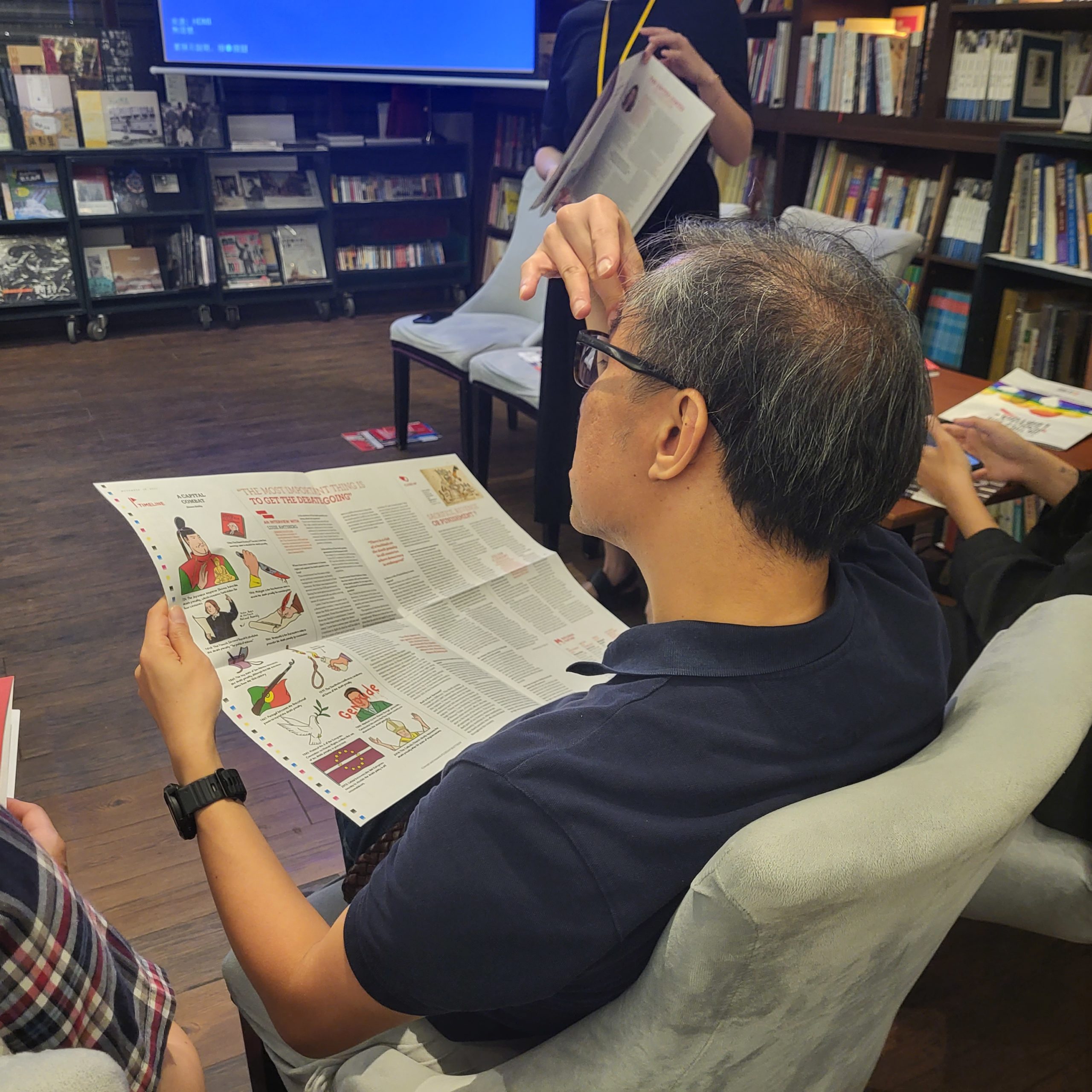

In the days following the seminar, ECPM members were invited to the youth forum organized by TAEDP and ADPAN: an opportunity for this new generation of activists to meet experts on the subject and discuss the various challenges they face in their fight. On the program: an introduction to existing international bodies and mechanisms for advocacy by Aurélie Plaçais, Executive director of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty; the construction of a 360° communications plan for the next World Day Against the Death Penalty; the powerful testimony of Hsu Tzu-chiang, a former death row prisoner in Taiwan; and a training session on press strategies to be considered by Kirsten Han, a journalist specializing in the subject with the Transformative Justice Collective in Singapore.

Another highlight was a visit to the Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial, which Fred Chin, a former political prisoner who was sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment after escaping a death sentence, took us on a tour of, recounting his story and the political implications of martial law imposed back then, which allowed anyone to denounce others who commit political offenses. To this day, Fred Chin still doesn’t know the precise reasons for his conviction. During Chiang Kai-shek’s forty years of White Terror, between 3,000 and 4,000 people were executed.

Focus on Taichung detention center

The youth forum ended with a visit to the Taichung detention center, which holds over 1,600 prisoners, 7 of whom have been sentenced to death. 4 death sentences have been confirmed. Those sentenced to death share the same cells as those awaiting trial or sentencing, and are generally treated in the same way.

The facility looks well-maintained. From afar, we greeted inmates at work. After visiting the general control center, where video surveillance of all the cells is installed, we crossed the detention corridor, where the contrast between the green, well-trimmed exteriors and the double-locked cells began to capture the delegation’s attention. In eight square meters at most, 3 to 4 people are crammed together. Death row inmates share a cell with a prisoner serving a light sentence. At the back of the room, a toilet and a basin of water for washing. No curtains, no walls to shield them from view: a way of distancing prisoners from their humanity. A table, or rather a board, folds against the wall. On the floor, nothing but hard concrete to doze on in the stifling heat of the Taiwanese summer. We cross paths with a man condemned to death who was taking part in a drawing class. Incarcerated for 18 years already, he shyly smiled at us and said a few words. One of his works was displayed on one of the walls.

Further on, the door of “life and death”. It opens only to those whose eyes will close forever within minutes of passing through. This large metal gate stands between the detention centre for those sentenced to death, and the prison for those serving long sentences. Historically, those whom the state decided to eliminate disappeared quickly, so no one bothered to transfer them to prison. Despite the long years they see passing today, this has remained the case in Taichung.

The execution chamber is half outside. The condemned man can ask the prosecutor for clemency one last time, and provide details of his case. But as he is only informed of his execution two to three hours before the fateful hour, the time to take a shower, gather his belongings and choose the clothes he will wear, he can only utter his last words and eat his last meal, which he also chooses. We are told that the person about to be executed is allowed alcohol and a cigarette.

His family will not be informed of the execution until the condemned man has been escorted to this room. Just enough time to inform the undertaker’s so that the body of the deceased can be taken away quickly. They will never be able to say goodbye. While visits are unlimited during detention, each one is potentially the last.

An anesthetic is administered to the convict, who then loses consciousness. He is laid on his stomach on a pile of sand covered with a cloth, in the middle of a space open to the outside. Within this enclosure, a small temple flanks one of the walls, where a final prayer is offered. At the far end, the door that will release his remains.

The executioner shoots him in the back, aiming for the heart at point-blank range. The coroner declares him dead. If he misses, a second bullet will finish him off. All division guards must witness the execution.

With financial support from the European Union, AFD and Fondation de France